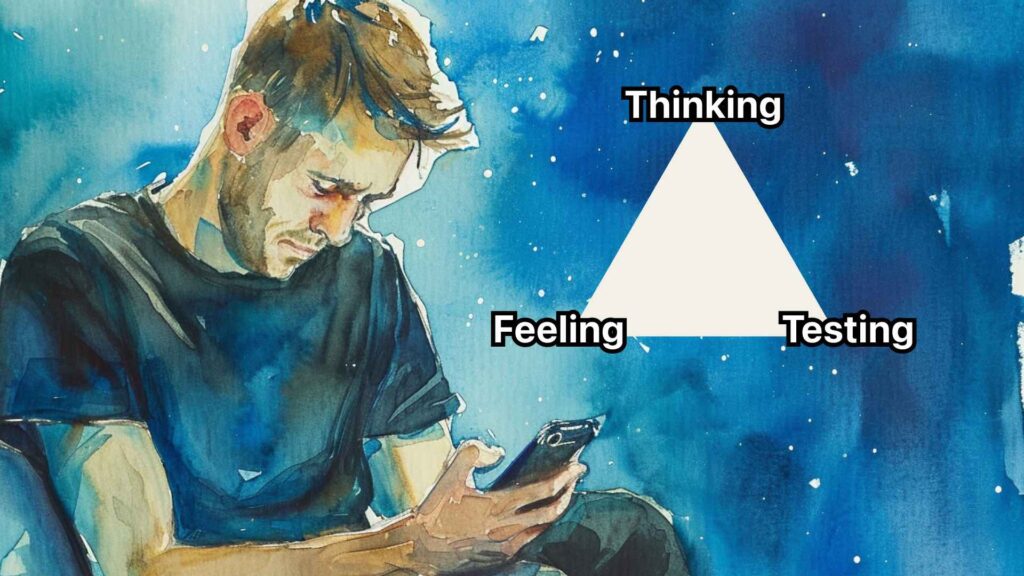

Chronic pain is a debilitating condition that can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life. While the physical aspects of chronic pain are often the focus of treatment, the role of negative thinking in coping with chronic pain cannot be overlooked. From a cognitive therapy perspective, negative thinking patterns can exacerbate the experience of pain and hinder effective coping strategies.

Cognitive therapy emphasizes the importance of examining and modifying our thoughts and beliefs to improve emotional well-being and coping abilities. One key technique used in cognitive therapy is Socratic dialogue, which involves asking questions to challenge and reframe negative thoughts. For example, if a person with chronic pain thinks, “I can’t do anything because of my pain,” a therapist might ask, “Is there any evidence to support this thought? Are there activities you can still engage in, even if they need to be modified?”

Through Socratic dialogue, individuals can begin to recognize cognitive biases that contribute to negative thinking. One common bias is the tendency to give more attention to negative experiences while discounting positive ones. This can lead to a distorted perception of reality, where the pain and its limitations become magnified, while moments of relief or accomplishment are minimized.

Our brains are wired to prioritize negative information as a survival mechanism, but in the context of chronic pain, this bias can be counterproductive. Constantly focusing on the pain and its negative impact can lead to feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and depression, which can further intensify the pain experience.

CBT & Chronic Pain

Cognitive therapy aims to help individuals identify and challenge these negative thinking patterns. By learning to recognize cognitive biases and reframe thoughts in a more balanced and realistic manner, individuals with chronic pain can develop more adaptive coping strategies.

For instance, instead of thinking, “My pain will never go away, and I can’t handle it,” a more balanced thought might be, “Although my pain is ongoing, I have managed to cope with it before, and I can continue to find ways to manage it effectively.” This reframing acknowledges the reality of the pain while also emphasizing the individual’s resilience and ability to cope.

In addition to challenging negative thoughts, cognitive therapy also encourages individuals to focus on the present moment and engage in activities that promote a sense of accomplishment and pleasure, despite the pain. This might involve setting realistic goals, pacing activities, and finding ways to adapt to limitations imposed by the pain.

By addressing negative thinking patterns and promoting more adaptive coping strategies, cognitive therapy can play a crucial role in helping individuals with chronic pain improve their quality of life. While the pain may not disappear entirely, learning to manage negative thoughts can reduce the emotional distress associated with chronic pain and foster a greater sense of control and resilience.

In conclusion, coping with chronic pain is significantly affected by negative thinking patterns, cognitive biases, and the brain’s tendency to prioritize negative information. Cognitive therapy, through techniques such as Socratic dialogue and thought reframing, can help individuals challenge these negative thought patterns and develop more adaptive coping strategies. By addressing both the physical and psychological aspects of chronic pain, individuals can work towards improving their overall well-being and quality of life.

Maladaptive vs. adaptive thinking

Let’s discuss each of these beliefs from the perspective of maladaptive vs. adaptive thinking in the context of chronic pain:

- “Chronic pain – Physical limitations”

- Maladaptive: “I can’t do anything because of my pain. My life is over.”

- Adaptive: “Although my pain limits some activities, I can still find ways to engage in meaningful pursuits within my current abilities.”

- “Chronic pain – Emotional impact”

- Maladaptive: “This pain will never end, and I can’t cope with it. I’m hopeless.”

- Adaptive: “Living with chronic pain is challenging, but I have the strength to manage my emotions and seek support when needed.”

- “Chronic pain – Coping strategies”

- Maladaptive: “Nothing works to ease my pain. I might as well give up.”

- Adaptive: “While there’s no perfect solution, I can experiment with different coping strategies to find what works best for me.”

- “Chronic pain – Social isolation”

- Maladaptive: “No one understands my pain. I’m better off alone.”

- Adaptive: “Although my pain may limit some social activities, I can still maintain connections with others who support and understand me.”

- “Chronic pain – Healthcare navigation”

- Maladaptive: “Doctors can’t help me. It’s pointless to keep trying.”

- Adaptive: “Navigating the healthcare system can be frustrating, but I will advocate for myself and continue seeking the care I need.”

- “Chronic pain – Treatment options”

- Maladaptive: “I’ve tried everything, and nothing helps. I’m out of options.”

- Adaptive: “While not all treatments will work for me, I will remain open to exploring new options and working with my healthcare team to find the best approach.”

- “Chronic pain – Self-management”

- Maladaptive: “I can’t manage this pain on my own. I’m helpless.”

- Adaptive: “I have the power to take an active role in managing my pain through self-care techniques, such as pacing, relaxation, and gentle exercise.”

- “Chronic pain – Acceptance”

- Maladaptive: “I refuse to accept this pain as a part of my life. It’s not fair.”

- Adaptive: “While I may not like my pain, accepting its presence allows me to focus on living my life to the fullest within my current circumstances.”

- “Chronic pain – Relationship impacts”

- Maladaptive: “My pain ruins all my relationships. No one wants to be around me.”

- Adaptive: “Chronic pain can strain relationships, but open communication and a willingness to adapt can help me maintain strong connections with loved ones.”

- “Chronic pain – Work and financial issues”

- Maladaptive: “I can’t work because of my pain. I’m a failure and a burden.”

- Adaptive: “Although my pain may impact my work, I can explore accommodations, modifications, or alternative income sources to maintain financial stability.”

- “Chronic pain – Identity and self-perception”

- Maladaptive: “Pain defines me. I’m nothing more than my limitations.”

- Adaptive: “While pain is a part of my life, it does not define my entire identity. I am still a multifaceted person with unique strengths and qualities.”

- “Chronic pain – Hope and resilience”

- Maladaptive: “There’s no hope for a better future. I’ll always be in pain.”

- Adaptive: “Although living with chronic pain is challenging, I maintain hope for better pain management and continue to build resilience in the face of adversity.”

Here’s a table showing the main patterns of maladaptive thinking in chronic pain and how to improve them through adaptive thinking:

| Maladaptive Thinking Pattern | Adaptive Thinking Alternative |

|---|---|

| All-or-nothing thinking: “I can’t do anything because of my pain.” | Realistic perspective: “Although my pain limits some activities, I can still find ways to engage in meaningful pursuits within my current abilities.” |

| Overgeneralization: “Nothing works to ease my pain.” | Openness to possibilities: “While not all treatments will work for me, I will remain open to exploring new options and working with my healthcare team to find the best approach.” |

| Discounting the positive: “I’ve tried everything, and nothing helps.” | Acknowledging progress: “I’ve made progress in managing my pain, and I will continue to explore new strategies that may provide relief.” |

| Jumping to conclusions: “Doctors can’t help me.” | Objective evaluation: “Navigating the healthcare system can be frustrating, but I will advocate for myself and continue seeking the care I need.” |

| Emotional reasoning: “I feel helpless, so I must be helpless.” | Separating emotions from facts: “Although I may feel helpless at times, I have the power to take an active role in managing my pain through self-care techniques.” |

| Labeling: “I’m a failure and a burden.” | Self-compassion: “Living with chronic pain is challenging, but I am doing my best to cope and maintain a meaningful life.” |

| Personalization: “My pain ruins all my relationships.” | Contextualizing: “Chronic pain can strain relationships, but open communication and a willingness to adapt can help me maintain strong connections with loved ones.” |

| Catastrophizing: “There’s no hope for a better future.” | Realistic optimism: “Although living with chronic pain is challenging, I maintain hope for better pain management and continue to build resilience in the face of adversity.” |

By recognizing these maladaptive thinking patterns and consciously replacing them with more adaptive alternatives, individuals with chronic pain can foster a more balanced and constructive mindset. This shift in perspective can lead to improved coping strategies, emotional well-being, and overall quality of life.