Fear of sleep and nightmares can significantly affect mental well-being, especially for those with OCD. This article explores how maladaptive beliefs contribute to sleep-related fears and the effectiveness of a cognitive-first approach through CBT to reshape thinking, enhance resilience, and improve overall mental health.

The Connection Between Dreams and Fear

In understanding the intricate relationship between dreams and fear, particularly within the context of individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), it becomes imperative to recognize how intrusive thoughts and anxieties influence not only waking life but also the realm of sleep. For many individuals with sleep OCD, the act of falling asleep transforms from a necessary biological function into a source of profound dread. This fear is often compounded by the nature of their dreams and intrusive thoughts that manifest while they navigate their sleep cycles.

Intrusive thoughts are a hallmark of OCD, with the condition often characterized by unwanted, distressing ideas that refuse to be silenced. During sleep, these thoughts can infiltrate dreams, leading to nightmarish scenarios that echo the very fears that plague the person during their waking hours. The fears can range from mundane anxieties about daily life to catastrophic thinking, where a simple act, such as going to bed, spirals into an overwhelming fear of nightmares, sleepwalking, or even loss of control. For example, an individual may lie awake, caught in a cycle of worry about experiencing a particularly vivid nightmare, leading them to avoid sleep altogether or create elaborate routines intended to “protect” them from the horrors their mind concocts at night.

The nature of sleep-related disorders often intertwines with maladaptive beliefs that fuel these fears. Individuals with sleep OCD may develop rigid thought patterns, such as the conviction that if they do not carefully prepare for sleep or engage in specific rituals before bedtime, they will inevitably experience distressing dreams. This thinking leads to a deterioration of sleep quality, not just from the nightmares themselves, but from the anxiety about the potential of experiencing them. Over time, these maladaptive beliefs form a feedback loop: the fear of having nightmares leads to anxiety and avoidance behaviors, which in turn can precipitate the very distressing sleep experiences they seek to avoid.

Common anxieties surrounding sleep in individuals with OCD include the anticipation of nightmares that feature themes of loss, inadequacy, or personal failure—all magnified through the lens of their obsessive thoughts. For instance, someone may dread going to sleep because they fear dreaming about failing to protect loved ones or making irreparable mistakes. Such catastrophic thinking amplifies their anxiety, leading to a paradox where the individual feels compelled to control their sleep environment obsessively, often engaging in rituals that temporarily relieve anxiety but ultimately reinforce the cycle of fear.

The impact of these unhelpful beliefs on sleep quality and overall mental health cannot be overstated. Sleep disruption is often linked to increased psychological distress, contributing to a decline in mood, cognitive functioning, and overall well-being. When sleep becomes a battleground of fear, the person may experience heightened irritability and even physical symptoms, such as fatigue and a weakened immune response, all of which further perpetuate the cycle of anxiety and fear surrounding sleep.

Conversely, a supportive thinking pattern can be cultivated through awareness and reframing of beliefs about sleep. Recognizing that nightmares are often an exaggerated manifestation of the mind’s fear can help reduce the grip of those fears. For instance, focusing on the understanding that nightmares, while distressing, do not equate to reality, can mitigate the anticipatory dread associated with bedtime.

In summary, the connection between dreams and fear, particularly for individuals with OCD, highlights a complex interplay of intrusive thoughts and maladaptive beliefs. By addressing these fears head-on and fostering healthier perceptions of sleep and dreams, individuals can work towards reclaiming their night’s rest and enhancing their quality of life. As we move forward to explore cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in the context of addressing these issues, it becomes essential to engage with the beliefs and thought patterns that have taken root in the landscape of their minds, paving the way toward transformative healing.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy as a Solution

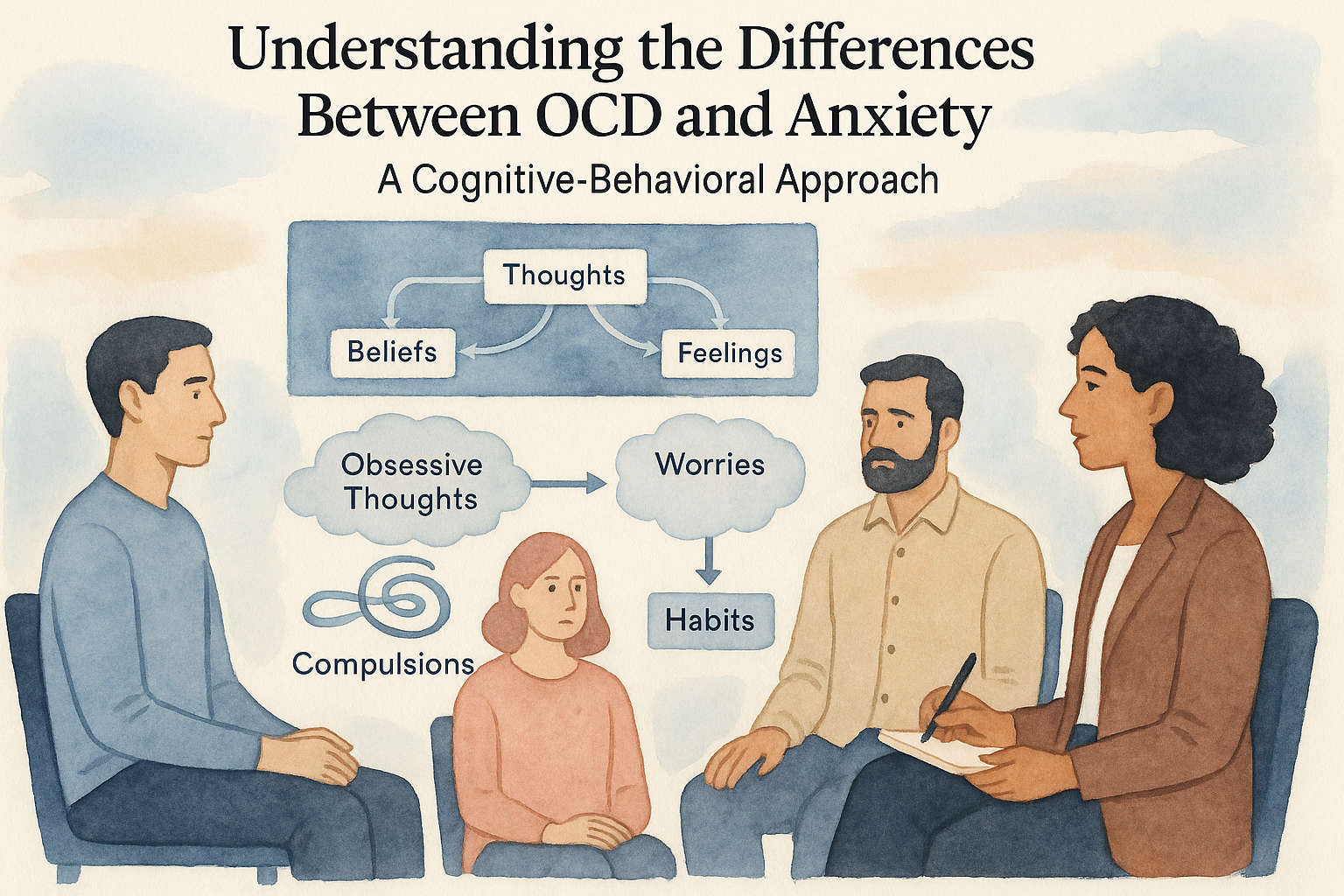

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has emerged as a powerful ally for individuals grappling with sleep-related obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). At its core, CBT offers a cognitive-first approach, targeting the maladaptive beliefs and cognitive distortions that fuel fear surrounding sleep and dreams. For those battling the relentless cycle of sleep OCD, the rigid patterns of thinking often exacerbate anxiety, leading to a heightened fear of both sleep itself and the nocturnal experiences that accompany it, such as nightmares or pervasive intrusive thoughts.

CBT operates on the principle that by reframing negative thoughts, individuals can alter their emotional responses and, ultimately, their behaviors. This method becomes particularly effective in confronting the irrational fears tied to sleep. For instance, an individual may harbor the belief that experiencing nightmares signifies a psychological weakness or that sleeping will inevitably lead to distressing dreams. CBT guides these individuals to recognize and challenge these thoughts, promoting a more flexible mindset.

Central to this therapeutic process are techniques such as cognitive restructuring and exposure therapy. Cognitive restructuring involves identifying negative thought patterns, evaluating their validity, and replacing them with more balanced alternatives. For example, instead of thinking, “If I sleep, I will have a nightmare,” a person can learn to reframe this belief to, “Having a nightmare does not define my ability to cope with anxiety.” This shift fosters resilience, allowing individuals to face the night with renewed confidence.

Exposure therapy complements cognitive restructuring by gradually exposing individuals to the fears associated with sleep in a controlled manner. This might involve imagining a scenario where a nightmare occurs or keeping a dream journal to confront the anxiety tied to intrusive thoughts. These exposures are designed to reduce the fear response over time, progressively desensitizing the client to the thought of sleep and its accompanying uncertainties.

Real-life case studies illustrate the profound transformations achievable through CBT. Consider Sarah, a 28-year-old artist with a long history of sleep OCD. Sarah would spend hours dreading the moment she had to turn off the lights, convinced that her dreams would descend into chaos, trapping her in a spiral of panic. Through CBT, Sarah learned to confront her fears directly. By collaborating with her therapist, she identified her predominant belief that nightmares held some sort of ultimate power over her wellbeing. Through cognitive restructuring, she reframed this belief to acknowledge that while nightmares are uncomfortable, they do not carry the same threat she once perceived.

As part of her exposure therapy, Sarah began journaling her dreams, including those that terrified her most. This practice allowed her to contextualize her fears, illustrating that even the most distressing dreams were just figments of her imagination, devoid of real-world consequences. Over time, Sarah noted a significant decrease in her pre-sleep anxiety and began approaching bedtime with a newfound sense of peace.

Similarly, Mark, a 34-year-old teacher, also found solace in CBT. Living under the constant burden of catastrophic thinking about sleep, he would ruminate on the potential for nightmares, which had previously led to insomnia. By participating in a structured CBT program, Mark confronted his beliefs about sleep as dangerous. He learned to practice mindfulness exercises that encouraged relaxation, along with cognitive techniques that helped debunk his fear of lost sleep leading to catastrophic outcomes. Mark’s journey toward recovery inspired him to develop healthy sleep hygiene practices, such as maintaining a consistent sleep schedule and creating a calming bedtime routine.

Through these case studies, we see that CBT serves as a bridge from the rigidity of fear-laden beliefs to a mindset that embraces flexibility and resilience. It equips individuals with the mental tools necessary to dismantle the barriers posed by sleep OCD, guiding them toward improved sleep patterns and a richer, more fulfilling life unburdened by fear of their dreams. With the right cognitive strategies in place, navigating the once-daunting realm of sleep transforms from a nightmare into a restorative journey, ultimately allowing dreams to become a source of creativity and renewal rather than dread.

Conclusions

In conclusion, understanding and addressing maladaptive beliefs through cognitive behavioral therapy is pivotal in managing the fear of sleep and dreams associated with OCD. By reshaping negative thinking patterns, individuals can achieve a more restful sleep and a healthier mindset.