Loneliness, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and the fear of being alone are deeply intertwined emotional struggles. This article delves into how maladaptive beliefs about these conditions can impact mental wellbeing. By understanding the cognitive patterns that contribute to these feelings, we can develop healthier, more resilient perspectives through cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Understanding Loneliness and Its Psychological Impacts

Loneliness is a potent emotional experience that can significantly impact an individual’s mental health. The perception of being isolated, whether physically or emotionally, can evoke feelings of despair, unworthiness, and disconnection from the world. Research has shown that loneliness can lead to a myriad of psychological issues, including anxiety and depression. For those grappling with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), the relationship with loneliness can become particularly complex and distressing.

Individuals with OCD often face intrusive thoughts that generate anxiety, compelling them to engage in rituals or compulsions in an attempt to alleviate those feelings. These compulsive behaviors can create barriers to social interaction. For example, a person dealing with contamination fears may avoid social gatherings entirely or find themselves excessively cleaning or sanitizing before any engagement, leading to a notable withdrawal from others. As a result, the individual not only battles the internal turmoil of their obsessions but also experiences loneliness as a byproduct of their avoidance strategies.

Take the example of Sarah, a young woman in her twenties, who has lived with OCD since childhood. She developed intrusive thoughts about harming others, leading her to believe that being around people might put them at risk. This perception caused her to withdraw from friends and family, creating a deep sense of isolation. Over time, the loneliness intensified her feelings of depression, leading to a vicious cycle: the more isolated Sarah felt, the more the compulsive thoughts worsened, and the more she reinforced the belief that distancing herself from others was the only solution.

Maladaptive beliefs, such as the notion that one’s worth is dictated by their ability to manage OCD symptoms, can further entrench feelings of loneliness. Many individuals with OCD feel like outcasts, burdened by their compulsions and ashamed by their perceived inability to conform to social norms. This can lead to the internal dialogue that friendships and social connections are not feasible, essentially shaping a self-fulfilling prophecy where belief in solitude reinforces actual isolation. Such beliefs are particularly alarming since they create significant obstacles to seeking help or building relationships that could provide support, further exacerbating their ongoing struggles.

The impact of loneliness on individuals with OCD can also be seen in the context of chronic loneliness versus transient loneliness. Chronic loneliness can have more insidious effects on mental health, often leading to a feeling of being stuck, as if the cycle of obsession, compulsion, and isolation has become a permanent state. Conversely, transient loneliness may arise in specific situations or phases of life but is often seen as temporary. In cases of OCD, chronic loneliness can exacerbate symptoms and impede recovery, creating a scenario where seeking social support feels insurmountably difficult.

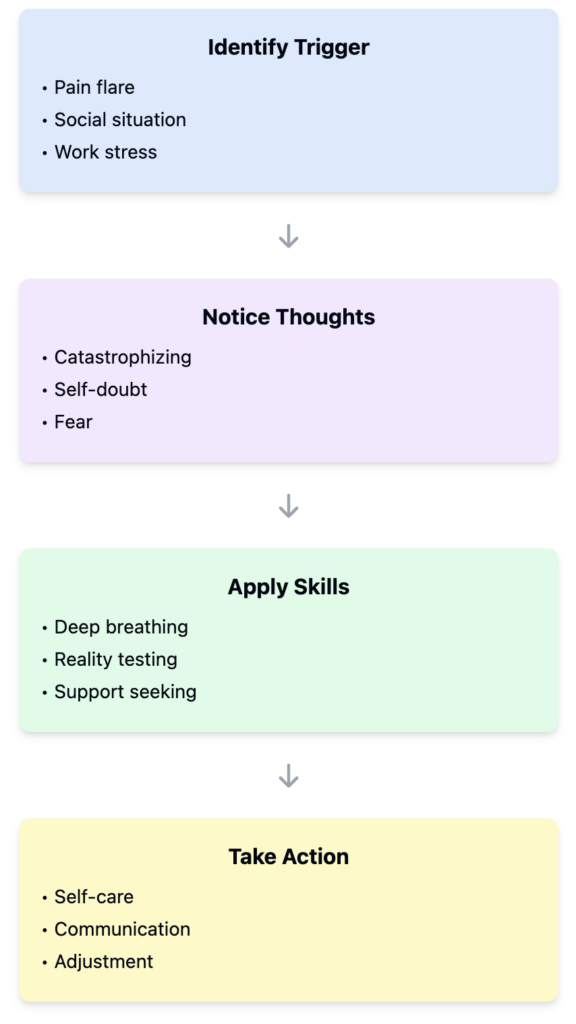

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) emerges as a valuable approach in addressing the interplay between OCD and loneliness. CBT identifies and alters maladaptive thought patterns, guiding individuals to challenge their beliefs surrounding social interactions and their compulsions. Through exposure and response prevention (ERP), a key component of CBT, individuals can confront scenarios that they might typically avoid due to fear or obsessive thoughts. By gradually engaging with the world around them, they can begin to dismantle the barriers established by their compulsions and reclaim their social lives.

Promoting healthy connections can also provide a buffer against the psychological turmoil linked to OCD and loneliness. Navigating relationships while managing OCD is undoubtedly challenging, but fostering a supportive network can be a transformative step toward healing. Cultivating understanding and empathy with friends and loved ones can dismantle the feelings of isolation, thereby helping individuals realize that they are not defined by their obsessions or compulsions, but rather by their resilience and their capacity to connect with others.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Its Relationship with Loneliness

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) manifests as intrusive thoughts and compulsions, often leading to significant distress. One of the most troubling aspects of OCD is how it can exacerbate feelings of loneliness by creating barriers to social interaction. Individuals with OCD may find themselves engaging in rituals that not only consume their time but also distract them from meaningful relationships. These compulsions can lead to misunderstandings among peers, fueling the belief that one is fundamentally different or flawed, which ultimately propels feelings of isolation. Consequently, the interplay between OCD and loneliness can create a vicious cycle where the very behaviors that individuals undertake to alleviate their anxiety further alienate them from social connections.

Real-life examples illustrate these dynamics poignantly. Consider a young professional who meticulously organizes their workspace due to their compulsive need for order. While this might initially seem benign, the time spent obsessively ensuring everything is perfect allows little room for social engagement, leading to missed lunch breaks and skipped after-work outings. Over time, the individual may come to view their compulsions as a definitive part of their identity, fostering a belief that they cannot partake in social interactions without the burden of their rituals. This reinforces their loneliness, as they may feel that no one can understand or accept them as they currently are.

Moreover, individuals with OCD often experience maladaptive beliefs that contribute significantly to their sense of loneliness. They may mistakenly think that their worth is solely tied to their ability to control their obsessions, leading to a lack of self-compassion and a distorted self-image. This cognitive distortion not only perpetuates their isolation but can also lead to depression, as they feel trapped within their compulsive behaviors. The belief that they cannot seek help because their condition makes them unworthy of love or companionship only deepens their sense of solitude and despair.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) offers a structured approach to help individuals reframe these maladaptive beliefs and develop healthier behavioral responses. Through CBT, patients can begin to understand that their thoughts do not define them and that their compulsions are symptoms of OCD rather than indicators of their character. For example, exposure and response prevention (ERP), a specific type of CBT, can gradually help individuals confront their fears in a safe environment, challenging their compulsive behaviors. By slowly facing situations that trigger their OCD without resorting to compulsions, individuals can start reclaiming their social lives and breaking the cycle of loneliness.

Additionally, CBT encourages the development of coping strategies that help individuals manage the anxiety associated with social interactions. These may include practicing mindfulness, where one learns to observe their thoughts and feelings without judgment. This practice aids in reducing the distress that often accompanies social situations for those with OCD. Gradually easing into social contexts by setting realistic and manageable goals can also help facilitate the reconnection with others, nurturing relationships that may have been neglected due to isolation caused by OCD.

In sum, understanding the relationship between OCD and loneliness is crucial for fostering mental wellbeing. By addressing the cognitive distortions and engaging in therapeutic practices such as CBT, individuals can learn to challenge their compulsions and dismantle the barriers that have led to their isolation. As they begin to engage more with others, they can pave the way toward genuine social connections, lessening their feelings of loneliness and enhancing their overall quality of life.

Navigating the Fear of Being Alone and Its Therapeutic Approaches

Fear of being alone, or autophobia, is a complex emotional response that often coexists with feelings of loneliness and the debilitating nature of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). This unique intersection presents notable challenges in understanding mental wellbeing, particularly for those who find themselves embroiled in the cycle of these interconnected experiences. The psychological origins of autophobia can be traced back to a variety of influences such as childhood experiences, trauma, and attachment styles. Individuals who have faced neglect or inconsistent caregiver presence may develop a heightened anxiety about solitude, perceiving it as a threat to their wellbeing.

The manifestations of the fear of being alone can vary widely. For some, it may present as intense anxiety when faced with solitude, prompting behaviors to seek out others even in mundane situations. Others may resort to compulsive actions to alleviate the anxiety associated with being alone, leading to a paradox where the very fear intended to be managed through social contact ultimately reinforces a sense of loneliness. This creates a cycle where the desire for companionship is overshadowed by the fear of solitude, perpetuating a state of emotional turmoil.

Psychologically, cognitive distortions play a pivotal role in the development and persistence of this fear. Many individuals might engage in catastrophic thinking, believing that being alone presages emotional or physical harm. This distortion can interrelate with OCD, where intrusive thoughts amplify existing fears and foster a sense of urgency to engage in compulsive behaviors. For instance, someone might worry that without constant reassurance from friends or family, they will succumb to an uncontrollable spiral of emotional pain or anxiety. This belief not only exacerbates feelings of isolation but also drains the individual’s capacity to engage meaningfully with others.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) stands out as an effective approach to understanding and reframing these erroneous thought patterns. Through CBT, individuals can be guided to identify and challenge their cognitive distortions related to loneliness and the fear of being alone. Techniques such as cognitive restructuring enable individuals to replace automatically negative thoughts with more balanced perspectives. For instance, rather than believing “I cannot handle being alone,” individuals can learn to reframe this thought as “I have the skills to manage my emotions when I am alone.”

Gradual exposure to the fear of solitude can also be an integral component of treatment. By gradually increasing the time spent alone in safe settings, individuals can begin to disassociate their fear from their experience of solitude. This exposure helps to reduce the panic response associated with being alone and allows for the learning of self-soothing techniques. Activities such as engaging in hobbies or practicing mindfulness can provide healthier alternatives to manage anxiety, directing focus inward rather than continuing the cycle of dependence on others for reassurance.

Furthermore, supportive examples from therapy sessions can illustrate the tangible benefits of confronting these fears. For instance, a client who previously relied heavily on friends for daily reassurance might be encouraged to spend a few hours alone engaged in an enjoyable activity. Through such experiences, clients often discover that solitude can foster creativity or serve as a space for self-reflection, ultimately leading to a greater appreciation of their own company.

As individuals gradually confront and restructure their beliefs surrounding solitude, they often experience improved emotional resilience, decreased anxiety, and a healthier relationship with themselves. This empowered approach enables individuals not only to tolerate being alone but to find joy in their own company—a crucial step in breaking the cycle of loneliness exacerbated by OCD and the fear of being alone. By understanding and navigating these interconnected challenges, individuals can embark on a journey toward holistic mental wellbeing.

Conclusions

In summary, addressing the linkage between loneliness, OCD, and the fear of being alone is vital for enhancing mental wellbeing. By fostering flexible thinking and challenging rigid beliefs, individuals can navigate their emotional challenges more effectively, improving their overall resilience and quality of life. CBT offers invaluable tools for this transformative process.